One of the most common muscle tears an athlete will have, is a tear of the hamstring muscles. It can put an athlete out for the season if it is not managed correctly. Hamstring tears can originate in various parts of the muscle (the origin or insertion, muscle tendon or muscle belly) and differ in severity of grade.

It is usually the result of over exerting the muscle during a sprinting style activity, although a fall, slip or sudden movement may also result in the injury occurring. An early, accurate, diagnosis by a physiotherapist and appropriate treatment will provide the best chance of returning safely to sport in a timely manner.

Anatomy

The hamstrings are a group of 3 muscles found in the posterior (rear) region of the thigh, extending from the buttocks to either side of the knee. They are some of the longest muscles in the body and are diarthoidial in nature, which means they extend across two joints (the hip and the knee). This last point is important when examining the action of the muscles, as both joints are implicated when an injury occurs.

The hamstrings can be divided into 2 groups; the medial (inside) and lateral (outside) groups. The medial group is made up of the semimembranosus and semitendinosis. The lateral group consists of the biceps femoris (long and short head). The primary function of the hamstrings is to flex (bend) the knee. It also has lesser functions to extend the hip and control rotary forces at the knee at end of range. They are primarily innervated by the tibial nerve.

The attachments of the hamstrings all originate at the ischial tuberosity (the short head of the biceps femoris originates at the posterolateral femur). The semitendinosisinsertion fans out in the shape of a ducks foot (pes anserine) and joins with the tendons of Sartorius and Gracilis as it attaches just above the tibial insertion of the medical collateral ligament of the knee. The semimembranosus is attached to the posteromedial tibia. The lateral insertion is less complicated although it incorporates its attachment at the head of the fibula with the arcuate complex at the posterolateral corner of the knee.

(NB: These variations in attachments are important as often an injury to the hamstring can implicate the medical collateral ligament or the posterolateral corner of the knee)

Causes

There are many different factors that can predispose an athlete to a tear:

- Poor flexibility of the muscles

- Reduced or side-to-side differences in strength of hamstrings

- Increased neural tightness, often arising from the lower back

- Inadequate warm up

- Fatigue

- Poor biomechanics or running pattern

- Return to activity prematurely following previous injury

Grade of Tear

Grade 1

- Usually a mild strain where cramping or tightness may be felt. Often there is some pain when the muscle is stretched or palpated.

Recovery: 5 days-4 weeks (depending on recurrence and ability to perform a sports specific program pain free).

Grade 2

- This grade usually is associated with more marked, instant, pain causing immediate cessation of activity. Athletes often describe a “ping” feeling, like a rubber band has snapped. This is confirmed again with palpation and stretch/contraction pain. There may be signs of swelling and often delayed bruising in and around the area.

Recovery: 4-6 weeks

Grade 3

- This is a complete rupture and is quite rare. Usually associated with a slip or fall into a splits position or jerking movement (often with water skiing). There will be immediate loss of strength. Pain is usually present, but not always. There will be a palpable area of swelling and a depression where there is a tear.

Recovery: Complete tears require surgical reattachment followed by a 3-6 month specific rehabilitation program

Physiotherapy and Rehabilitation

Optimal recovery from an injury to the hamstrings requires accurate diagnosis and grading. The length of time from injury is important in determining a suitable program. An individualised rehabilitation program should follow a basic timeline of:

- acute/subacute phase

- repair/remodelling phase

- functional/return to activity phase

Timelines for the use of Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) has been debated with some professionals opting for immediate use (to prevent adverse effects from the injury that may interfere with tissue remodelling) and others suggesting a delay of 2-4 days post injury (to prevent interference with the inflammatory response and the laying down of new muscle fibers). It is best to discuss this with your treating physio or doctor.

Acute/subacute Phase (1-14 days)

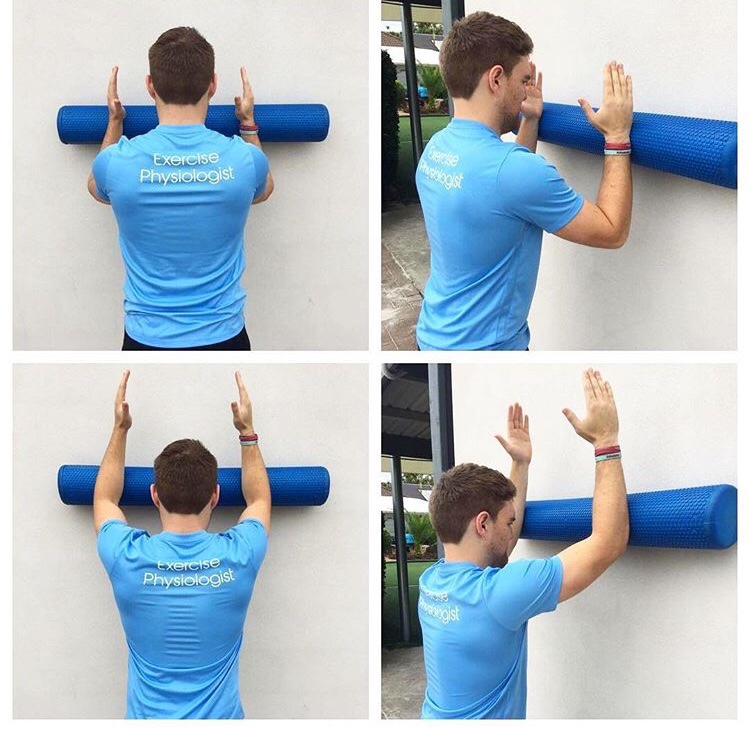

The goals of this phase include reduction of pain and swelling and restoration of normal range of motion (ROM). This initial treatment follows the general principles of RICE (rest, ice, compression, elevation) and may involve the use of aides with more severe injuries. Once pain is reduced, gentle soft tissue massage and ROM exercises can begin, progressing from passive to active-assisted to active movements.

Eventually flexibility and strengthening exercises can be started, commencing with closed chain. Cardiovascular exercise can commence, such as cycling, swimming and light jogging. A graduated running program can be commenced once pain free and is progressed accordingly (see running program).

It is important to perform adequate strengthening, flexibility and balance exercises as advised by your physiotherapist. Returning to activity too early can pre-dispose to re-injury.

Repair/remodeling Phase (1-6 weeks)

During this phase strengthening can be progress to open chain concentric exercises, initially with low weight and reps and slowly increased. This can then be progressed to eccentric exercises but should be done carefully at first so as to avoid over exertion and lumbo-pelvic compensations. Strength should be progressed to reflect similarity with the unaffected leg. At the same time flexibility and balance (proprioception) should be worked on and progressions through the running program.

Other modalities such as ice/heat, dry needling, taping and joint mobilisation may also be used throughout this phase.

Functional/return to activity Phase (2 weeks-4 months)

By this phase there should be no pain, normal gait pattern, good strength and ROM. Functional, sport specific exercises can gradually be incorporated into the program after careful discussion with your physiotherapist.

This is where the graduated running program is very useful as is provides a suitable progression of intensity and volume of activity. Plyometric and dynamic exercises can also be added to improve speed and power. Extrinsic variables such as use of equipment and balls can also be introduced in this phase. The patient should be reminded of the importance of a warm up and should continue doing flexibility exercises.

Surgical Repair

The need for surgical intervention is rare but generally required for grade 3 complete ruptures when the tendon has come off the bone. The time frame from injury to surgery is variable with good results in both acute and chronic cases (although acute intervention is preferred).

References