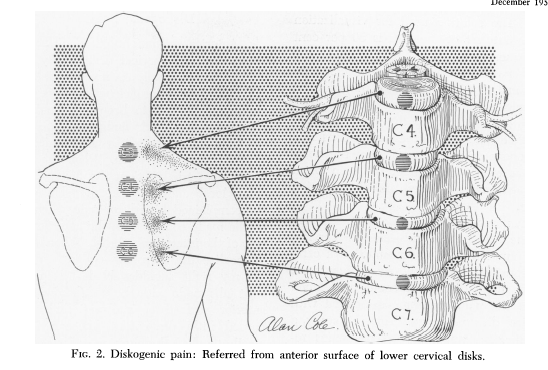

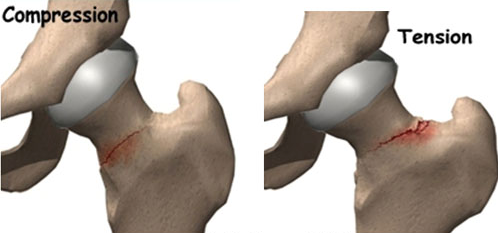

Cloward’s sign is a clinical indicator that plays a crucial role in diagnosing cervical spine disorders. First described by Dr. Ralph Cloward in the mid-20th century, this sign refers to the referral of pain from the cervical spine to the medial scapular region. It typically occurs when there is compression or irritation of a cervical disc, especially in the C4–C7 region. The resulting scapular pain can easily be mistaken for a primary shoulder or upper back issue, making accurate diagnosis essential.

What makes Cloward’s sign unique is the consistency of referred pain patterns. For example, irritation of the C5–C6 disc may present as deep, dull pain around the inner border of the scapula. This can often confuse both patients and clinicians, leading to unnecessary shoulder investigations or treatments. The presence of Cloward’s sign strongly suggests that the source of pain is cervical rather than musculoskeletal in the shoulder blade region.

Why Physiotherapy Is Uniquely Positioned to Diagnose and Manage Cloward’s Sign

Physiotherapists are trained to conduct detailed musculoskeletal assessments, enabling them to distinguish between local shoulder pathology and referred pain from the cervical spine. Through movement testing, palpation, and neural provocation tests (like the Spurling’s or Upper Limb Tension Tests), a physiotherapist can pinpoint the true source of a patient’s pain.

Moreover, physiotherapists often work collaboratively with GPs, Sports Physicians and Orthopaedic specialists. This multidisciplinary approach ensures patients receive the most accurate diagnosis and evidence-based treatment.

Four Effective Physiotherapy Treatment Options for Cloward’s Sign

Cervical Mobilisation and Manual Therapy

Various joint mobilisation techniques can target stiffness in the cervical spine, especially in the mid-to-lower cervical segments. By restoring normal joint movement, physiotherapists can reduce nerve root irritation and disc mobility, thereby decreasing referred scapular pain. Manual therapy can also include soft tissue work on surrounding muscles that may become tight due to compensatory guarding and spasm.Neural Mobilisation Techniques

Neural mobilisation, often referred to as "nerve gliding," is an effective way to address nerve irritation. These gentle exercises aim to improve the mobility of the affected cervical nerve and reduce mechanosensitivity. For example, median nerve glides are frequently prescribed for C6–C7 related symptoms. As neural tension reduces, referred pain often subsides.Postural Education and Ergonomic Advice

Poor posture, particularly forward head posture, is a significant contributor to cervical disc pressure. Physiotherapists provide targeted postural correction strategies to reduce strain on the cervical spine. This includes advice on workstations, sleep posture and daily activities. Sustained postural improvements through improved strength and awareness can often lead to long-term symptom resolution.Targeted Strengthening and Stability Exercises

Probably the most important and effectice part of treating a Cloward’s sign is the rehabilitative exercises that strengthen deep neck flexors, scapular stabilisers, and postural muscles help prevent recurrence. These exercises improve spinal alignment and reduce the likelihood of future disc irritation. Programs are tailored to each individual’s condition and activity level, promoting active recovery.

Conclusion

Cloward’s sign is a powerful clinical clue that can help identify cervical spine pathology manifesting as scapular pain. Physiotherapists, with their holistic assessment skills and evidence-based interventions, are ideally positioned to both diagnose and manage this condition. Through a combination of manual therapy, nerve mobilisation, ergonomic education, and targeted strengthening exercises, patients can achieve meaningful relief and long-term recovery—without the need for surgery, unnecessary imaging or prolonged medication use.